April 30, 2017

Visual Artists Rights Act Review

In 1990 Congress added the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) to the Copyright Law as new Section 106A. Section 106A provides:

106A Rights of certain authors to attribution and integrity

(a) Rights of Attribution and Integrity. — Subject to section 107 and independent of the exclusive rights provided in section 106, the author of a work of visual art —

(1) Shall have the right —

(A) to claim authorship of that work, and

(B) to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of any work of visual art which he or she did not create;

(2) Shall have the right to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of the work of visual art in the event of a distortion, mutilation, or other modification of the work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation; and

(3) Subject to the limitations set forth in section 113(d), shall have the right

(A) to prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation, and any intentional distortion, mutilation, or modification of that work is a violation of that right, and,

(B) to prevent any destruction of a work of recognized stature, and any intentional or grossly negligent destruction of that work is a violation of that right.

(b) Scope and Exercise of Rights — Only the author of a work of visual art has the rights conferred by subsection (a) in that work, whether or not the author is the copyright owner. The authors of a joint work of visual art are co-owners of the rights conferred by subsection (a) in that work.

(c) Exceptions —

(1) The modification of a work of visual art which is a result of the passage of time or the inherent nature of the materials is not a distortion, mutilation, or other modification described in subsection (a)(3)(A).

(2) The modification of a work of visual art which is the result of conservation, or of the public presentation, including lighting and placement, of the work is not a destruction, distortion, mutilation, or other modification described in subsection (a)(3) unless the modification is caused by gross negligence.

(3) The rights described in paragraphs (1) and (2) of subsection (a) shall not apply to any reproduction, depiction, portrayal, or other use of a work in, upon, or in any connection with any item described in subparagraph (A) or (B) of the definition of “work of visual art” in section 101, and any such reproduction, depiction, portrayal, or other use of a work is not a destruction, distortion, mutilation, or other modification described in paragraph (3) of subsection (a).

(d) Duration of Rights.—

(1) With respect to works of visual art created on or after the effective date set forth in section 610(a) of the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, the rights conferred by subsection (a) shall endure for a term consisting of the life of the author.

(2) With respect to works of visual art created before the effective date set forth in section 610(a) of the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, but title to which has not, as of such effective date, been transferred from the author, the rights conferred by subsection (a) shall be coextensive with, and shall expire at the same time as, the rights conferred by section 106.

(3) In the case of a joint work prepared by two or more authors, the rights conferred by subsection (a) shall endure for a term consisting of the life of the last surviving author.

(4) All terms of the rights conferred by subsection (a) run to the end of the calendar year in which they would otherwise expire.

(e) Transfer and Waiver.—

(1) The rights conferred by subsection (a) may not be transferred, but those rights may be waived if the author expressly agrees to such waiver in a written instrument signed by the author. Such instrument shall specifically identify the work, and uses of that work, to which the waiver applies, and the waiver shall apply only to the work and uses so identified. In the case of a joint work prepared by two or more authors, a waiver of rights under this paragraph made by one such author waives such rights for all such authors.

(2) Ownership of the rights conferred by subsection (a) with respect to a work of visual art is distinct from ownership of any copy of that work, or of a copyright or any exclusive right under a copyright in that work. Transfer of ownership of any copy of a work of visual art, or of a copyright or any exclusive right under a copyright, shall not constitute a waiver of the rights conferred by subsection (a). Except as may otherwise be agreed by the author in a written instrument signed by the author, a waiver of the rights conferred by subsection (a) with respect to a work of visual art shall not constitute a transfer of ownership of any copy of that work, or of ownership of a copyright or of any exclusive right under a copyright in that work.

A work of Visual Art to which Section 106A applies is defined as:

(1) a painting, drawing, print, or sculpture, existing in a single copy, in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author, or, in the case of a sculpture, in multiple cast, carved, or fabricated sculptures of 200 or fewer that are consecutively numbered by the author and bear the signature or other identifying mark of the author; or

(2) a still photographic image produced for exhibition purposes only, existing in a single copy that is signed by the author, or in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author.

A work of visual art does not include—

(A)(i) any poster, map, globe, chart, technical drawing, diagram, model, applied art, motion picture or other audiovisual work, book, magazine, newspaper, periodical, data base, electronic information service, electronic publication, or similar publication;

(ii) any merchandising item or advertising, promotional, descriptive, covering, or packaging material or container;

(iii) any portion or part of any item described in clause (i) or (ii);

(B) any work made for hire; or

(C) any work not subject to copyright protection under this title.

While it seems hard to quibble with the idea of protecting the integrity of artistic works, VARA (and it should be noted similar state laws) seem to punish those who are foolish enough to allow their property to be the canvas. Perhaps for this reason many VARA decisions seem to stretch the law to avoid what the court might perceive as an unjust result.

Review

Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, Inc.In Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, Inc., 71 F.3d 77 (2nd. Cir. 1995), the Second Circuit’s determination that a very large “walk-through sculpture” occupying most, but not all, of the building’s lobby was a work-made-for-hire that saved the building owner from liability under VARA. In the words of the district court:

The artwork consists of a variety of sculptural elements constructed from recycled materials, much of it metal, affixed to the walls and ceiling, and a vast mosaic made from pieces of recycled glass embedded in the floor and walls. Elements of the work include a giant hand fashioned from an old school bus, a face made of automobile parts, and a number of interactive components. These assorted elements make up a theme relating to environmental concerns and the significance of recycling.

In Phillips v. Pembroke Real Estate, Inc., 459 F.3d 128 (1st Cir. 2006), the First Circuit’s determination VARA does not include site-specific art (art that is integrated into a site) allowed a park to be redesigned without VARA liability.

Chapman Kelley v. Chicago Park District

In Chapman Kelley v. Chicago Park District, 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011), the Seventh Circuit’s questionable determination that Kelley’s Wildflower Works was not protected by copyright because it was not fixed in a tangible medium, allowed the City to reconfigure Kelley’s oval flower beds into smaller, rectangular beds, and change some of the flowers, without liability under VARA.

In Pavia v. 1120 Avenue of the Americas Associates, 960 F.Supp. 620 (S.D.N.Y. 2003), the district court held that VARA applied to a sculpture created before its enactment, but not to alleged acts of mutilation that occurred before enactment. Thus the district court dismissed Philip Pavia’s VARA claims resulting from defendants movement of his “The Ides of March” sculpture from a Hilton Hotel Lobby to a warehouse.

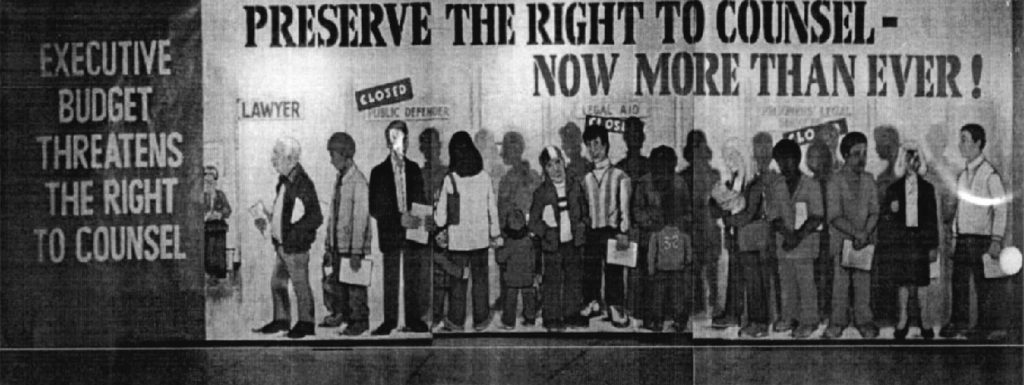

In Pollara v. Seymour, 344 F.3d 265 (2nd Cir. 2003) the Second Circuit’s determination that a hand-painted banner was not a work of visual art, saved a city employee from liability under VARA for removing the banner, which was installed at public plaza without a permit.

In Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art Foundation, Inc. v. Buchel, 593 F.3d 38 [93 U.S.P.Q.2d 1632] (1st Cir. 2010), although the First Circuit found that VARA applied to unfinished art, its determination that neither partially covering the unfinished work with tarpaulins nor displaying the unfinished work in its entirety violated VARA.

In Martin v. City of Indianapolis, 982 F.Supp. 625 (S.D.Ind. 2007), the district court granted summary judgment to Jan Martin for the city of Indianapolis’ destruction of his Symphony # 1 sculpture after his offers to donate and move the sculpture to another site for a cost of $8000.

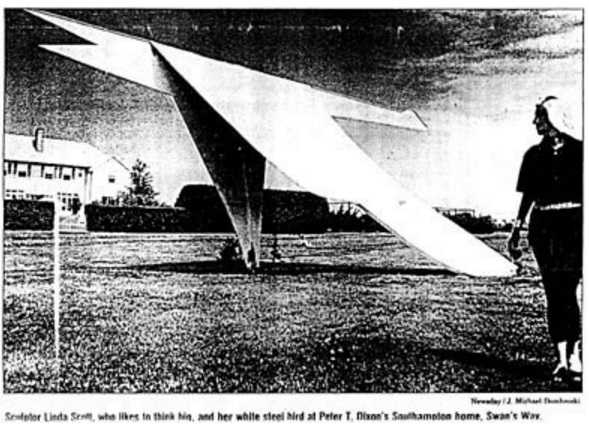

In Scott v. Dixon, 309 F.Supp.2d 395 (E.D.N.Y. 2004), the district court found that Scott’s sculpture of a swan that the Dixons asked Scott to build in their backyard, was not a work of sufficient stature to merit protection under VARA, even though some of her other works may have attained that stature.

In Hunter v. Squirrel Hill Associates, L.P., 413 F.Supp.2d 517 (E.D.Pa. 2005), the district court found that the VARA action brought by the painter of a mural damaged by water leakage against a roof repairer was time-barred.

In Flack v. Friends of Queen Catherine Inc., 139 F.Supp.2d 526 (S.D.N.Y. 2001), Audrey Flack, an artist commissioned to create a statute of Queen Catherine of Braganza, namesake of the borough of Queens in New York City, sued Friends of Queen Catherine, Inc. the non-profit organization managing the project. Flack sculpture of the head of the statue was left outside and was damaged, and rather than paying Flack to resculpt the face, one of her assistants was hired to do the work, so the statute could be completed. The district court rejected the claim that leaving the model outside violated VARA because damage from the passage of time or the inherent nature of the materials is excluded. The court also rejected that the repair of the model violated VARA because conservation is also excluded.

Board of Managers of Soho International Arts Condominium v. City of New York

In Board of Managers of Soho International Arts Condominium v. City of New York, 2003 WL 21403333 (S.D.N.Y. June 17, 2003) the district court denied the parties cross motions for summary judgment, noting that plaintiff failed to establish the sculpture was not removable from the building (and thus not protected under VARA), and defendant failed to established that it was removable (and thus entitled to limited production under VARA). See Board of Managers of Soho Intern. Arts Condominium v. City of New York, 2005 WL 1153752, 75 U.S.P.Q.2d 1025 (S.D.N.Y. 2005).

Cohen v. G & M Realty LP

In Cohen v. G & M Realty LP, 988 F.Supp.2d 212 (E.D.N.Y. 2003), the district court denied a preliminary injunction against the demolition of the buildings on which plaintiff’s aerosol artwork were created.

In Kleinman v. City of San Marcos, 597 F.3d 323 (5th Cir. 2010), the Fifth Circuit determined that a car-planter did not qualify as a “work of visual art” under the VARA, and thus was subject to regulation by the city.

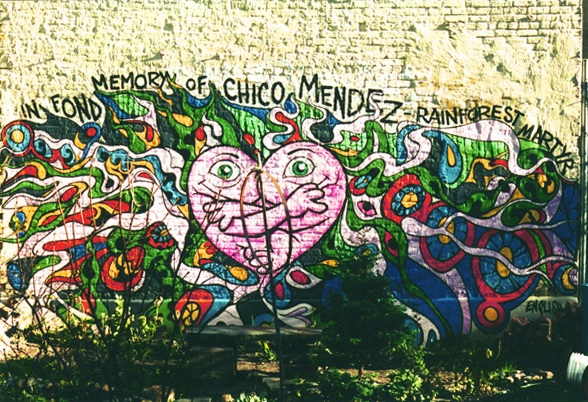

In English v. BFC&R East 11th Street LLC, [97 Civ. 7446(HB)] 1997 WL 746444 (S.D.N.Y. 1997), the district court denied artist’s motion for preliminary injunction and granted the developer’s motion for summary judgment, finding that the murals were placed illegally on the property, and thus not entitled to protection under VARA.

In Leicester v. Warner Bros., 232 F.3d 1212 [57 U.S.P.Q.2d 1001] (9th Cir. 2010), the Ninth Circuit determined that artist Andrew Leicesters contributions to the design of the streetscape around the 801 Tower in Los Angeles (featured in Batman Forever) became part of a unitary architectural work, and was not entitled to separate protection under VARA.

In Cheffins v. Stewart, 825 F.3d 588 [119 U.S.P.Q.2d 1094] (9th Cir. 2016), the Ninth Circuit affirmed the determination that a mobile replica of 16th-century Spanish galleon, built from used school bus, was a work of applied art, and thus not protect by VARA, when it was burned by the owner of the land on which it was stored, so that the bus could be sold as scrap.

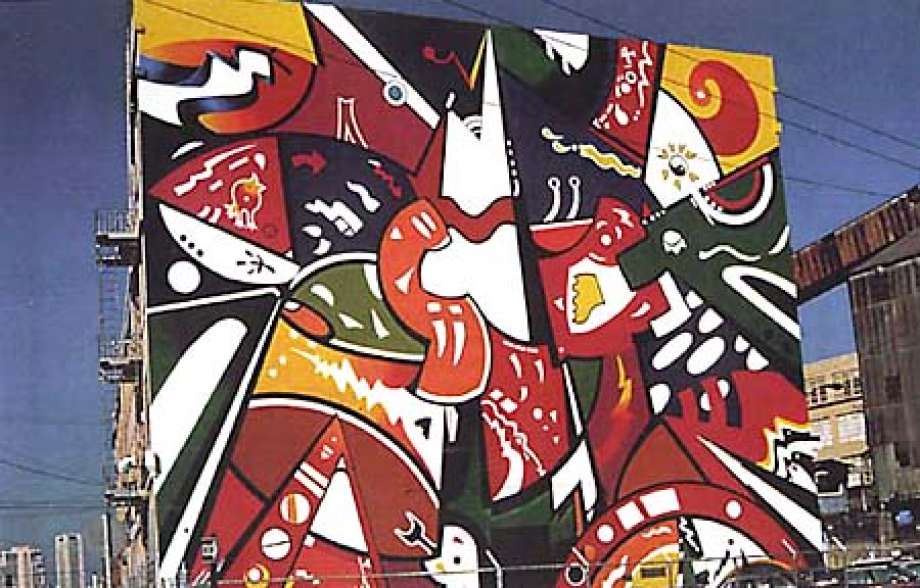

In Cort v. St. Paul Fire and Marine Ins. Companies, Inc., 311 F.3d 979 (9th Cir. 2002), the Ninth Circuit held that claims under VARA for covering over artist Jesus “Chuy” Campusano’s Lilli Ann mural did not constitute advertising injury covered by defendant’s commerical insurance policies.

In Hanrahan v. Ramirez, [2:97–CV–7470 RAP RC] 1998 WL 34369997 (C.D. Cal. 1998), Artist Mary B. Hanrahan won default judgment against the lessees of Avenue Liquor Store in West Ventura that painted over her mural.

In Whalen v. United Food and Commercial Workers Local 135, [14–CV– 3017 W(BLM)] 2015 WL 4659213 (S.D. Cal. 2015), the district court granted and part and denied in part defendant’s motion to dismiss, finding that artists John and Jeanne Whalen did state a cause of action under VARA for the Union’s painting over their mural “Providing The Feast,” located on the Union’s wall. See, Whalen v. United Food and Commercial Workers Local 135, 2016 WL 2866875 (S.D.Cal. 2016)

Kammeyer v. United States Army Corps of Engineers

In Kammeyer v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, [15–869 JGB (KKx)] 2015 WL 12765463 (C.D.Cal. 2015) the court granted the Corps’ motion to dismiss artist Ronald Kammeyer’s VARA lawsuit to stop the Corps from Bicentennial Freedom Mural in Corona, California, but allowed Kammeyer to refile. See, also, Kammeyer v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, [15–869 JGB (KKx)] 2015 WL 12791408 (C.D.Cal. June 3, 2015)

In Jackson v. Curators of the University of Missouri, [11–4023–CV–C–MJW] 2011 WL 5838432 (W.D. Mo. November 21, 2011), the district court denied the University’s motion to dismiss artist Paul Jackson’s VARA claims for mistreatment of his Tiger Spot mosaic installed on campus.

Romero v. California Department of Transportation

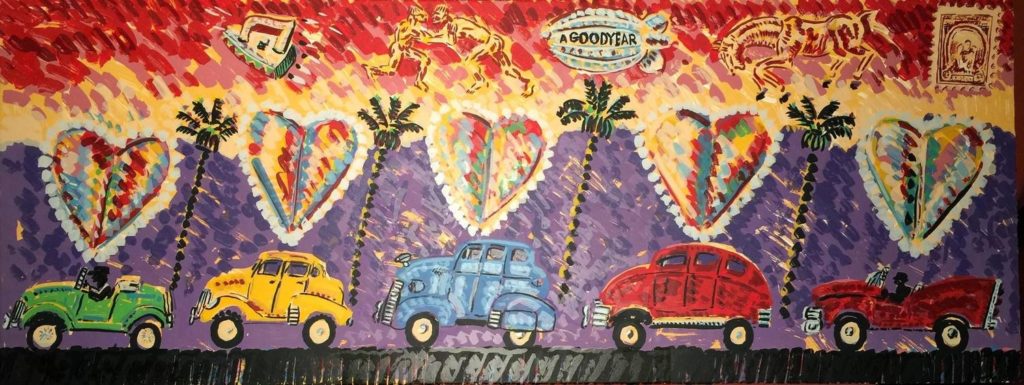

In Romero v. California Department of Transportation, [ 08–8047 PSG (FFMx)] 2009 WL 650629 (C.D.Cal. March 12, 2009), the district court granted CalDOT’s motion to dismiss Frank Romero’s VARA claim for painting over his “Going to the Olympics” mural rather than cleaning the graffiti from it.